This isn’t the blog post I thought I’d be writing. I first had a go at sharing ideas on here in 2020, with my piece about returning to work from maternity leave in a pandemic. Lots has happened since then.

At Middle Child we returned to live performance, opened our new home at Bond 31, switched to the four-day working week and were successful in securing funding from the Arts Council for the next three years.

Meanwhile, I’ve had my second child and participated in two learning fellowships – I graduated from the Clore Leadership Programme last summer, and I am currently an Arts and Philanthropy Senior Fellow learning more about leadership and fundraising.

In my last first piece, I wrote about adapting to the pandemic and the pressures of running the company alongside being a first-time mum. The conflicted emotions of being back at work – joy, guilt, exhaustion, energy – and some of my coping mechanisms.

After returning a second time, this piece isn’t the piece I thought I’d be writing, because after five years leading the company alongside our artistic director Paul I decided to step down from my role as executive director and joint CEO of Middle Child, to take a new role at Parents and Carers in Performing Arts (PiPA).

This hasn’t been an easy decision. I care deeply about the company, the team and the artists and audiences we serve, but with two young children, I need to recalibrate my life to my current caring commitments and find balance for myself.

So, as I write to you for the last time, I thought I’d share a few reflections on the last five years.

It’s not just what you do, it’s the way that you do it

Creating award-winning theatre, securing a new home and working with so many talented people, has been everything. I am so proud that we’ve done all this whilst putting people at the heart of what we do and championing flexibility and inclusivity, because it’s not just what you do but the way that you treat people whilst you’re doing it.

We’ve done this in a range of ways. We’ve started talking about wellbeing at all levels of the organisation. We’ve included it in briefings and introduced wellbeing check ins during meetings and rehearsals. We’ve advocated for those with caring commitments and joined PiPA – more about them later. We’ve piloted financial support for parents and carers and adopted more flexible working practices on productions. We’ve reviewed all our policies and put things in place for things like proper maternity and sick pay. Most fundamentally, we’ve shifted to the four-day week. Our artistic director Paul has written about this from his point of view, but I wanted to share a few thoughts from my perspective.

The four-day week

Switching the company to the four-day week felt like a significant ask. It is hard to put your head above the parapet and advocate for big changes and it’s important to recognise that it takes a lot of emotional labour to drive change, particularly when the outcome will have an impact on you. The biggest shift at Middle Child has been creating a culture of caring, where we can talk – at board meetings, at our desks and in the rehearsal room – about what it’s like being a parent or carer and what we need to do our best in the job. I hope that doing this authentically from my own point of view has created space for others to say what they need and serves the company by retaining staff and better supporting freelancers.

However, it would be disingenuous for me to say it has solved everything. For me personally, I have realised what leadership is like and the toll it’s taking on me in this moment, so it’s time for me to change it up a bit.

Part of that is balancing full-time work with my caring commitments. Whilst the four-day week has been incredibly responsive to some of those needs, reducing extortionate childcare costs and allowing me more time with my children, I am with them both on the day I am not in the office so it’s not the mental and physical break I need to re-charge.

Pre-children I definitely reaped the benefits that Paul talked about, but post children I am usually chasing mine around soft-play or trying to stop them jump in the duck pond at the park. I need to call this what it is – a working day of a different and unpaid kind. I’m adapting to the fact that reducing the hours I am in paid work doesn’t necessarily reduce the number of hours I work overall. In terms of finding balance, there’s time for paid work and caring for my children but what about time for me?

I am an ambitious person and I have often equated working harder, over longer hours, with working better. When I started working four-days a week I had some unlearning to do, as well as finding the confidence to challenge this assumption for myself I had to advocate for it at board level. Ironically, I have never worked harder than in the last few years of working four days a week. I’ve learnt that balancing paid work with caring is mentally, physically, and emotionally exhausting.

I am still incredibly proud that we made the shift to a four-day week at Middle Child, and thankful to Paul and the board for their trust and piloting it in the first place. I know that as I move on, I am leaving behind a more balanced environment for everyone to do their job in, creating a more sustainable and resilient future.

Being the executive director is also a demanding job with lots of responsibility all the time. Whilst I absolutely can do it, I have asked myself if I want to do it at this stage in my life. Of course, I want the nourishing and rewarding career that I have worked so hard for, but I also want to be a present parent and a balanced human, and I’ve realised being CEO isn’t working for me right now. Not the outcome I expected having just completed a leadership fellowship, but I was reminded by a Clore fellow that things don’t last forever, and I can decide to be a CEO again in the future if it’s right. I also recognise that whilst this is the right decision for me, we’re all different and balancing parenting with paid work comes in all shapes and sizes. Not to mention the privilege that I have choices and can make changes that work better for me and my family in the first place.

Next steps

Where does all this leave me? Well, I’ve realised I need to work part-time so I can create space for myself outside of work and children to rest and recalibrate so that I can show up as my best self. I need to work flexibly and from home for a bit, so I am not rushing around all the time and frazzling my nervous system. I need to make the decision that is right for me now, not the one I thought I would be making pre-children or in my twenties when being an executive director was my main goal. I need to be confident and know this isn’t about shying away from hard work, it’s about recognising all the different roles in my life that take work. It’s about making work, work for me.

Working with an organisation with flexibility at its core is essential, and I am delighted to join the team at PiPA as business development and programme manager. It’s an extraordinary opportunity for me to combine my passion for the performing arts with my commitment to ensuring parents and carers thrive in the sector. Although I am sad to have left Middle Child there really isn’t a better company I could join, and I can’t wait to be a part of the change I want to see for my industry.

Middle Child is vital

This leads me to some final thoughts on Middle Child. I know first-hand how important it is to be able to access great theatre in Hull. Running this company from my home city, working with so many talented people and sharing our shows with our fantastic audiences has been everything. I wholeheartedly believe that Middle Child is essential, supporting a thriving arts ecology and making sure anyone, no matter their background or where they come from, can make and enjoy great theatre.

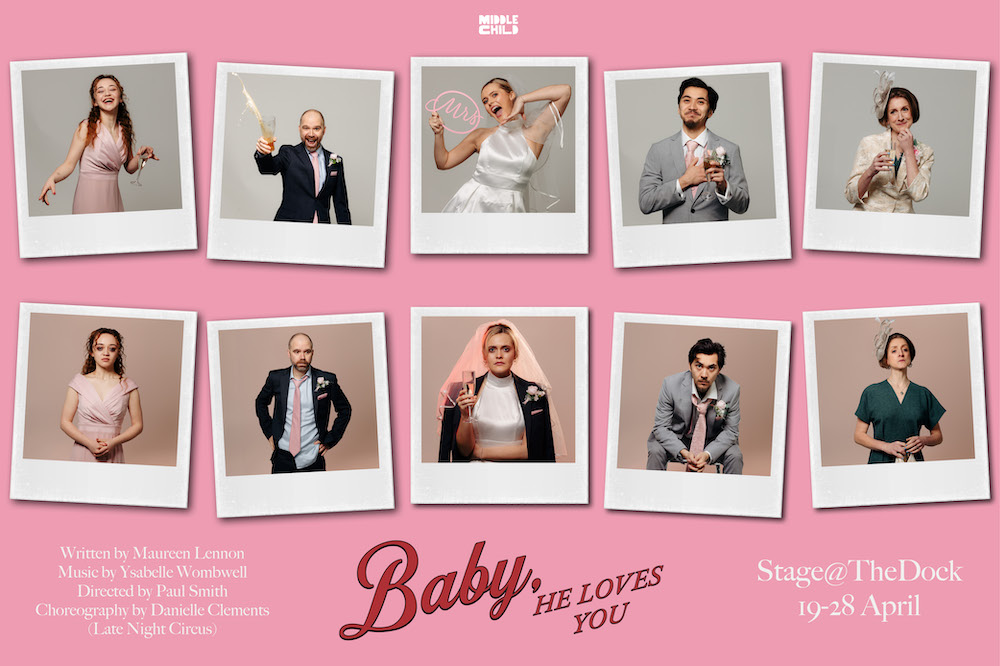

Middle Child has gone from nine students wanting to change the world to the organisation it is today in a relatively short period of time. It is a small, dynamic and responsive organisation that can do things differently, try out ideas and be the change we want to see. It invests in people early in their careers, not only through commissioning and its artist development programme Reverb, but also in the core staff team who are all doing their roles for the first time. Artists who have worked for Middle Child have gone on to work for London’s Royal Court, the National Theatre and the BBC and my maternity covers have gone on to senior positions at Battersea Arts Centre and HOME Manchester. It really is a hotbed of talent.

For all the success and the joy – singing Sweet Caroline amongst the audience at panto will stay with me for a very long time – there have been challenges. We all know it has been an intense few years and we are living through uncertain times. Whilst it’s isn’t easy to talk about the difficulties we face, Middle Child has been open and authentic, whether that’s asking for help finding a new home or talking openly about why we need to raise ticket prices for panto. The company has also taken time and care to actively listen and respond to changing needs, whether that’s creating the Recover, Restart, Reimagine programme to help freelancers recover from the pandemic or asking audiences to choose the title for panto.

Whatever challenges and opportunities Middle Child faces going forward, I know the team will continue to actively listen to your needs and respond.

Thank you

So now to the thank yous.

Firstly to the original company members who wanted to change the world. You really did and I can’t thank you enough.

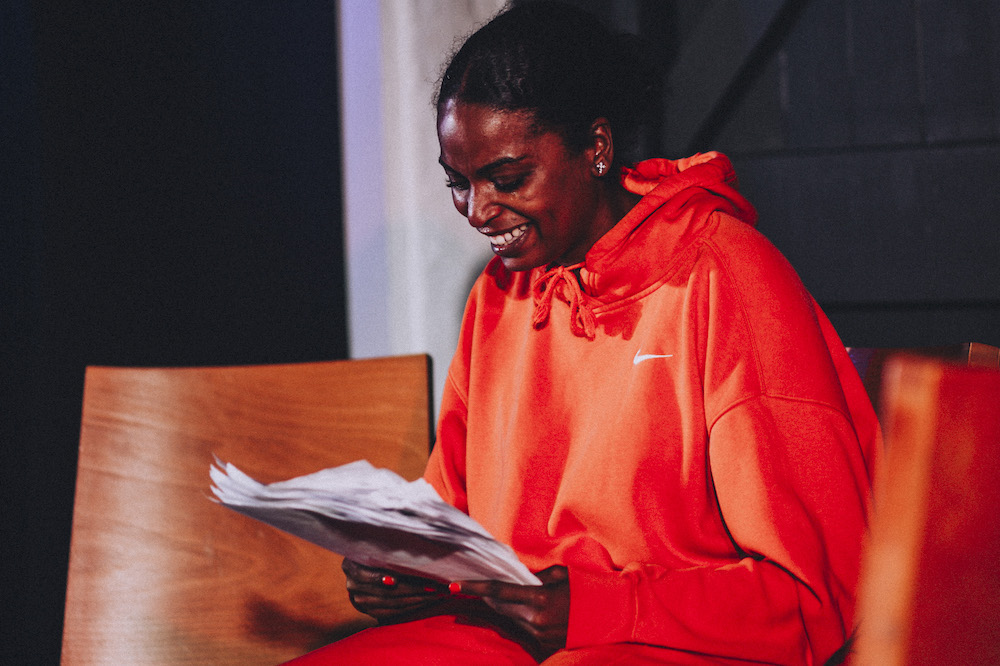

To the artists and freelancers we work with, you are the lifeblood and we couldn’t do it without your talent and craft.

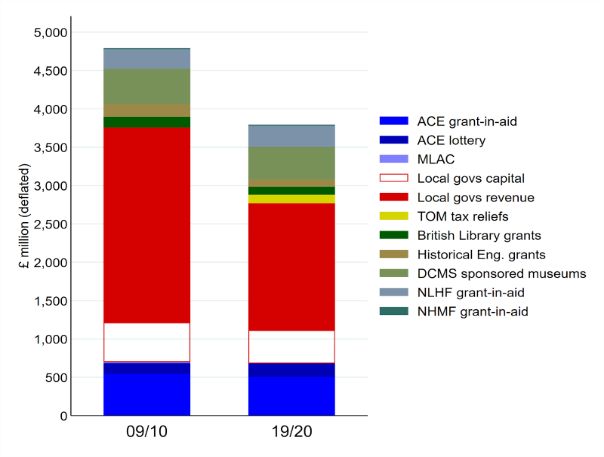

To the funders who put their money where it’s needed and make such a huge difference to creativity in Hull.

To the board for leading us through uncertain times, being critical friends and always helping us put things into perspective.

To executive director maternity covers Rozzy and Hattie for looking after the company so well and handing something back that was richer because of their care and skill.

To the extraordinary team. Artistic director Paul for his leadership and energy, finance and operations manager Emily for her commitment and conviction, audience development manager Jamie for his taste and vision, literary manager Matt for his care and craft, assistant producer Erin for her curiosity and enthusiasm, finance manager Terri for her support and guidance and new senior producer Sarah for her brilliance and joining for the ride.

Finally, to the audiences, participants, volunteers, supporters – we couldn’t do this without you and your support. Whether that’s buying a ticket for a show, volunteering at panto, liking our social media content, popping into the library or supporting us as a Middle Child Mate. It all makes a difference, and I hope you know that you are supporting the next generation of theatre-makers and sharing untold stories in Hull and beyond.

So, this isn’t the blog post I thought I’d be writing, but I am okay with that because in these changing times we need to prioritise our values and listen to our needs. We need to make the decision that is right for us now, not the one we thought we’d make or that others would make for us. We need to do whatever it takes to look after ourselves so we can show up as the best version of ourselves for the many roles we do.

Finally, as I say goodbye to Middle Child as executive director and joint CEO, I will be saying hello to you in the audience and advocating for the company in new ways. Maybe I will apply for the next writers scheme, I will definitely become a Middle Child Mate, because Middle Child is essential and I can’t wait to see what the company achieves next as it takes on the challenges and opportunities it faces with authenticity, leadership and sheer star quality.