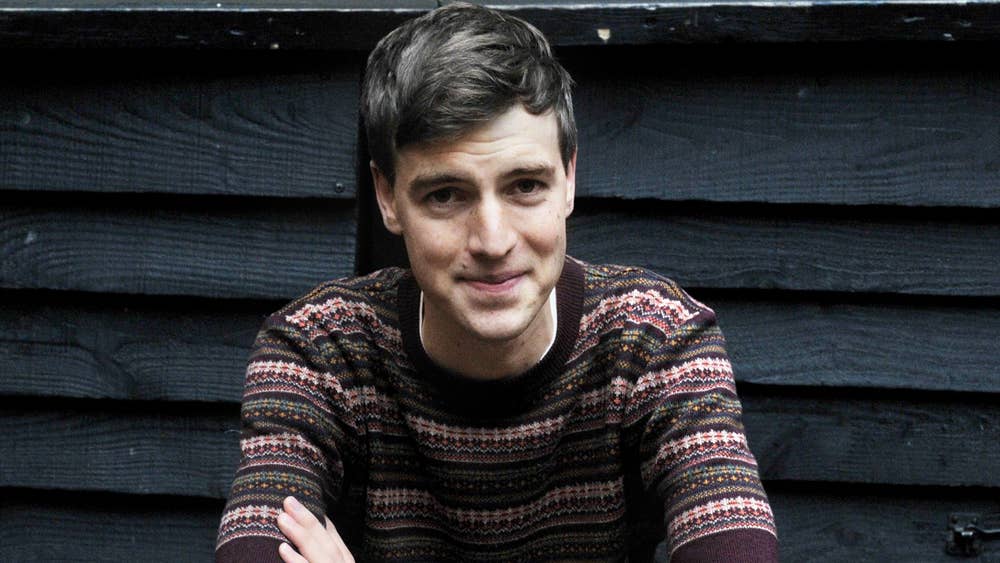

By Tom Wells, associate artist

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #1: Voice

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #2: Character and Monologue

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #3: Dialogue and Scenes

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #4: Making Worlds

This is the fifth and final playwriting blog. I’d like to say I’ve saved the best til last, but I worry that’d be a fib. Planning doesn’t sound very exciting, because it isn’t. It is important though, and really helpful – if you put a bit of work in before you start writing you’ll save yourself lots of time once you get going, or get stuck. A good plan will mean you’ve properly thought about the story you want to tell in your play and the way you want to tell it. You can still leave room for surprises and unexpected bits – it’s absolutely fine, and fun, to adjust things as you go along – but hopefully you’ll find it reassuring for your idea to have a loose shape before you start. I do, anyway.

Exercise One

For this exercise, the challenge is to write a plan for your play which fits with the model we’ve been using to think about story structure, below. Think of the play you’re hoping to write. If it’s your first go at writing a play, aim for between five and ten minutes. Try to think how the story you’re trying to tell in your play would fit with the five bits of the structure. Don’t worry if you don’t know all the answers yet – it’s just as useful to know which parts need a bit of extra thinking about. Spend ten minutes thinking of and writing down a very loose plan which fits these five story beats:

- A character wants something, and sets out to get it;

- Things go well – the character manages to get a bit nearer to the thing they want;

- Things start to go badly – the character comes up against obstacles, but keeps going;

- Things go very wrong for the character – it looks like the thing they wanted is out of reach, unachievable;

- Some kind of resolution: maybe the character gets the thing they wanted; maybe the character doesn’t, and has to give up; maybe they get something different, something they need.

It’s important to say: just because the plan focuses on the story of one character doesn’t mean you can only have one character in your play. It’s really possible that the main character needs to get the thing they want from another character, or their mate goes along to help them and accidentally gets in the way a bit (I have often been this friend). It’s good to focus on the main story you’ll be telling in your play though, and that probably means focusing, for now, on the journey of one character.

Exercise Two

This is a bit of good old-fashioned character building, as we did in week two. A reminder of the exercise: for each character in your play, draw a stick figure version of them. Give them names and ages. And then write things about them in the space around the drawing. Just anything that comes to you. Label them with the information. See if you can write down everything about that character you can think of. Spend a good bit of time with each character, getting to know them and writing down the interesting details of their lives. Let yourself be a bit surprised with some of the things you figure out about them. Enjoy it. See the best in them. Then take them with you into the next exercise.

Exercise Three

This will seem very familiar from last week’s post, but it’s also really useful. So: think about the world of the play. Imagine it on stage. Draw a plan of it from above. Label it with specific details.

Think about how a character might enter or leave the space and write these down. Think about the furniture or landscape, stories attached to them, or memories. Write these down too. Label it with details which add colour and life to the world. Think about some of the stories which have happened in the space, and write them on the plan. Think about the characters who belong there, and add them in too. Start to build a sense of the world of a play which might happen there. Fill the space with life, if you can.

Now, take a minute to look at your rough plan, your character sketches, and the world you’ve put together for your play. You’ve got everything you need to get going. Here’s a couple of things to think about as you’re cracking on.

The first is a bit of practical advice about putting scenes together, if the play you’re writing has more than one scene. I read something once that said in a comic, the space between two frames or images is called the gutter. In order to make sure the story is moving forward something always needs to happen in the gutter, so that by the next drawing the story has moved on and the reader has to fill in the gaps a bit, build the story themselves. They can feel the energy of that forward momentum, which makes them feel part of the story.

The same thing needs to happen in the gap between scenes in a play. The best way I’ve heard of doing this is to start each scene as late as you can, so the audience has a bit of catching up to do, a bit of figuring out from the very beginning, and then finish the scene as early as you can, so the audience is left with loose ends and questions that can only be answered in scenes that come later. Arrive late, get out early, which as an introvert is also a good strategy for parties.

Rather than telling a whole story in a scene, a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, make sure that the scene has just two of these – either a middle and an end, so the audience is watching the action unfold and, at the same time, figuring out what’s just happened, or how the characters got there; or a beginning and a middle, so the audience is left to wonder what the outcome of the scene is, something which can be answered in a later scene. Put a few of these together, different choices for each scene, and you will have an energetic, forward-moving structure for your play.

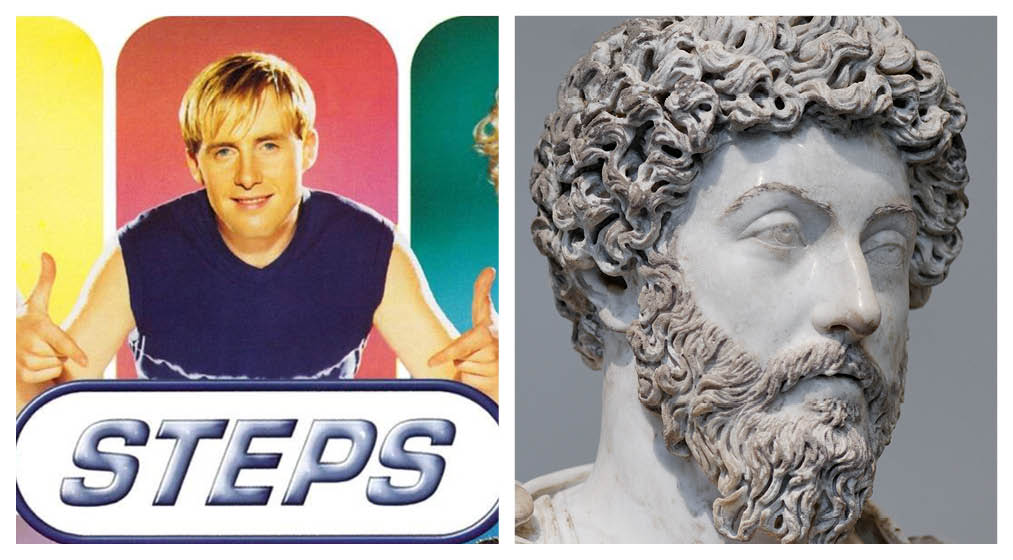

The second is a quote I like: ‘it loved to happen’. For the past ten years, I thought this was a quote by H from Steps, but a quick Google has shown it’s actually attributed to the ex-Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Not to worry. I think it’s a really lovely thing to think about while you’re planning your play and writing your first draft. Write something only you could, the characters and stories you think are important, the play you want to see in the world. Write something that just flipping loves to happen. I think it’ll feel magic when it does

Feel free to share your writing with us on social media: simply tag @middlechildhull on either Twitter, Instagram or Facebook.